Wherever they went, in their voyages of land, sea, and mind, Europeans planted their own memories on whatever they contacted. In his book The Idea of Africa, V. Y. Mudimbe writes, “The geographic expansion of Europe and its civilization . . . submitted the world to its memory.” Mapping, which involves exploration and surveying, was followed first by naming and then by ownership. Mapping was the imperial road to power and domination. The fictive figure of Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine comes to mind. Even in his last gasps of breath, Tamburlaine is still hankering after a map: Give me a map; then let me see how much is left for me to conquer all the world, . . .

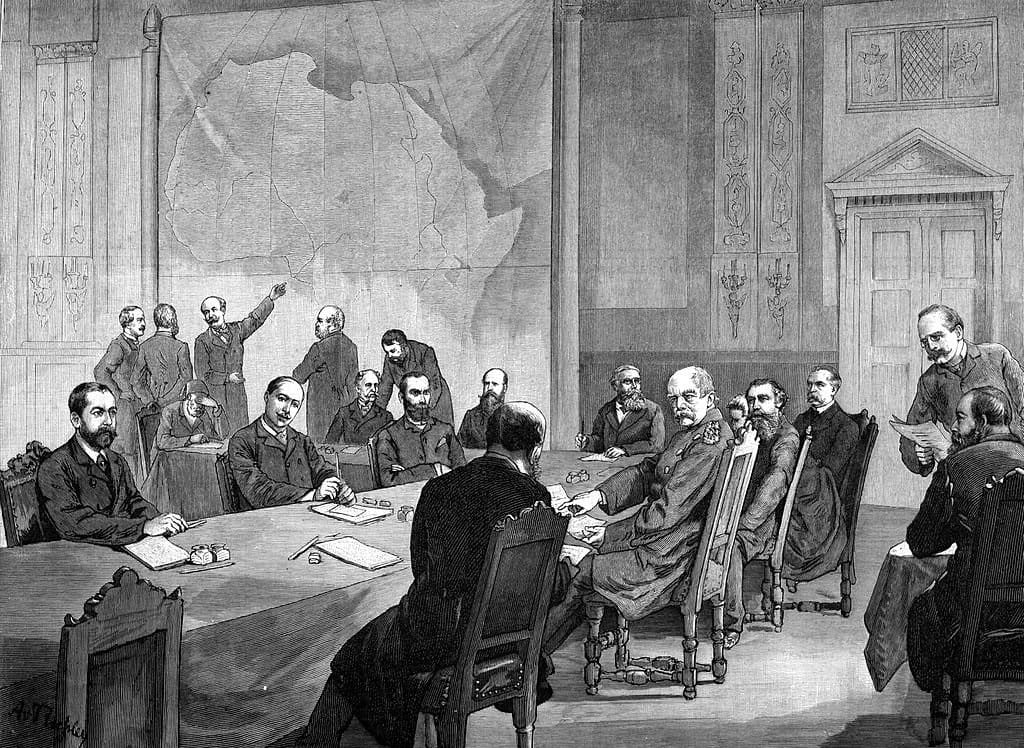

A map in his hands, the world left for him to conquer includes Egypt, Arabia, India, Nubia, Ethiopia, and across the tropical line to Zanzibar, then north until he has all of Africa under his sword. The imaginary Tamburlaine dies before he can achieve world domination—he does not even know America exists, but his real-life historical children do know and carry on his renaissance ambitions of mapping, naming, and owning.

Columbus goes west across the Atlantic and, despite finding people inhabiting the lands, he calls the region he finds there “New Hispaniola.” Later the whole landmass is named America after Amerigo Vespucci. Much later we get New York, New Jersey, New Britain, New Haven, and of course New England. Maori territory, Aotearoa, becomes New Zealand. An entire Asian/Pacific landscape becomes the Philippines. Africa is no different. The African landscape is blanketed with European memory of place. Names like Port Elisabeth, King Williamstown, Queenstown, and Grahams - town cover the landscape that King Hintsa died protecting from foreign occupation. Wetlands (formerly Kĩrũngiĩ) and Karen now become the names of the lands Waiyaki once traversed.

Lake East Africa, the main source of the River Nile and hence the base of one of the major world civilizations, is named for Victoria. But all these places had names before—names that pointed to other memories, older memories. To the Luo people of Kenya, Lake East Africa was known as Namlolwe (meaning endless body of water).

A European memory becomes the new marker of geographical identity, covering up an older memory or, more strictly speaking, burying the native memory of place. Now and then, as in the case of New Zealand and even America, one can see the older and newer memories in contention with place names; but generally, after the planting of European memory, the identity of place becomes that of Europe.

Even today, years after achievement of political independence, the African continent is often identified as Anglophone, Francophone, or Lusaphone. Europe has also planted its memory on the bodies of the colonized. This phenomenon is not peculiarly European but, rather, is in the nature of all colonial conquests and systems of foreign occupation. In his attempt to remake the land and its peoples in his image, the conqueror acquires and asserts the right to name the land and its subjects, demanding that the subjugated accept the names and culture of the conqueror.

When Japan occupied Korea in 1906, it banned Korean names and required the colonized to take on Japanese ones. But one might ask: What is in a name? It is said that a rose by any other name would still smell as sweet; however, the truth is that its identity would no longer be expressed in terms of roses but, instead, would assume that of the new name. Names have everything to do with how we identify objects, classify them, and remember them. The encounter between the unnamed man and Crusoe in Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe readily comes to mind. “. . . I was greatly delighted with him,” says Crusoe, “and made it my business to teach him everything that was proper to make him useful, handy and helpful; but especially to make him speak, and understand me when I spoke; and he was the aptest scholar that ever was. . .”

The education program that Crusoe sets up for the man begins with names. Crusoe does not even bother to ask the man’s name: “[And first I let him know that his name should be Friday, which was the day I saved his life; . . . I likewise taught him to say ‘Master,’ and then let him know that was to be my name.” Subject and master become the terms of their exchange. Even simple greetings—How are you, Friday? I am fine, Master—express their unequal relationship. Friday’s body no longer carries any memory of previous identity to subvert the imposed identity.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

What is in your name?