Rainmaking rituals differ from tribe to tribe and from nation to nation. The Pedi also have their way to invoke the god of rain, but again the rituals differ from village to village. In most cases there are special people who have the inspiration or power to perform the art of rainmaking. In the Pedi tribe there is what is called a moroka [rainmaking traditional doctor]

In times of drought the village chief calls upon the advice of his or her khudu-thamaga [the managers of the chief's kraal] or his or her batseta [chief's right-hand men] - frequently close relatives) for a kgothakgothe [general meeting] in which the issue of drought is discussed. In the discussion the moroka is allowed to set his or her price for invoking storm-free rain. Normally each household in the village is required to contribute a certain amount of money towards the moroka. A sheep, goat or cow could also be one of the demands of the moroka, before he or she can make rain (the kind of demand depends on the moroka).

It is believed that a drought in a village might be caused by the conflicts amongst the residents in the village or even within the chieftaincy or the leaders of the different traditional leaders. To ensure good rains, leaders must resolve their conflicts and come together for rituals to worship their ancestral spirits. Sometimes a drought could be caused by the moroka if he or she has not been paid by the village. In that case the villagers have to make things right with the moroka, for him or her to release the rain to fall in the village again (Vufhuizen 1997:31).

In most cases a moroka would argue that the rain would depend on the amount of money paid to him or her. This means that if he or she is paid late or too little then he or she will not be able to choose a cloud that will produce good rain for the village, since other Baroka2 [rainmaking traditional doctors] will have already chosen clouds that produce good rains. According to Pedi tradition, a moroka is able to fight storm rain and that again depends on the amount paid to him or her.

Other Baroka use a magical horn to invoke rain and this horn is placed in a place believed to be sacred. Only the family of a moroka has access to that place. Moreover, caves can also be used as shelter for the rain medicine. The Pedi and the Tswana make regular sacrifices of corn and beer to the spirits associated with these caves and shelters. The sacrifices are usually accompanied by prayers for rain and crop fertility.

In areas where there are no caves a moroka places his or her rain medicine at a selected place in the backyard garden and builds reeds around it.

The Lubedus also use the magical horn to invoke a rain. In 2008 the Mokotos and the Modjadjis fought over the magical horn, which made the Modjadji family pull out of the rainmaking ceremony and perform their own ritual that failed to produce rain.

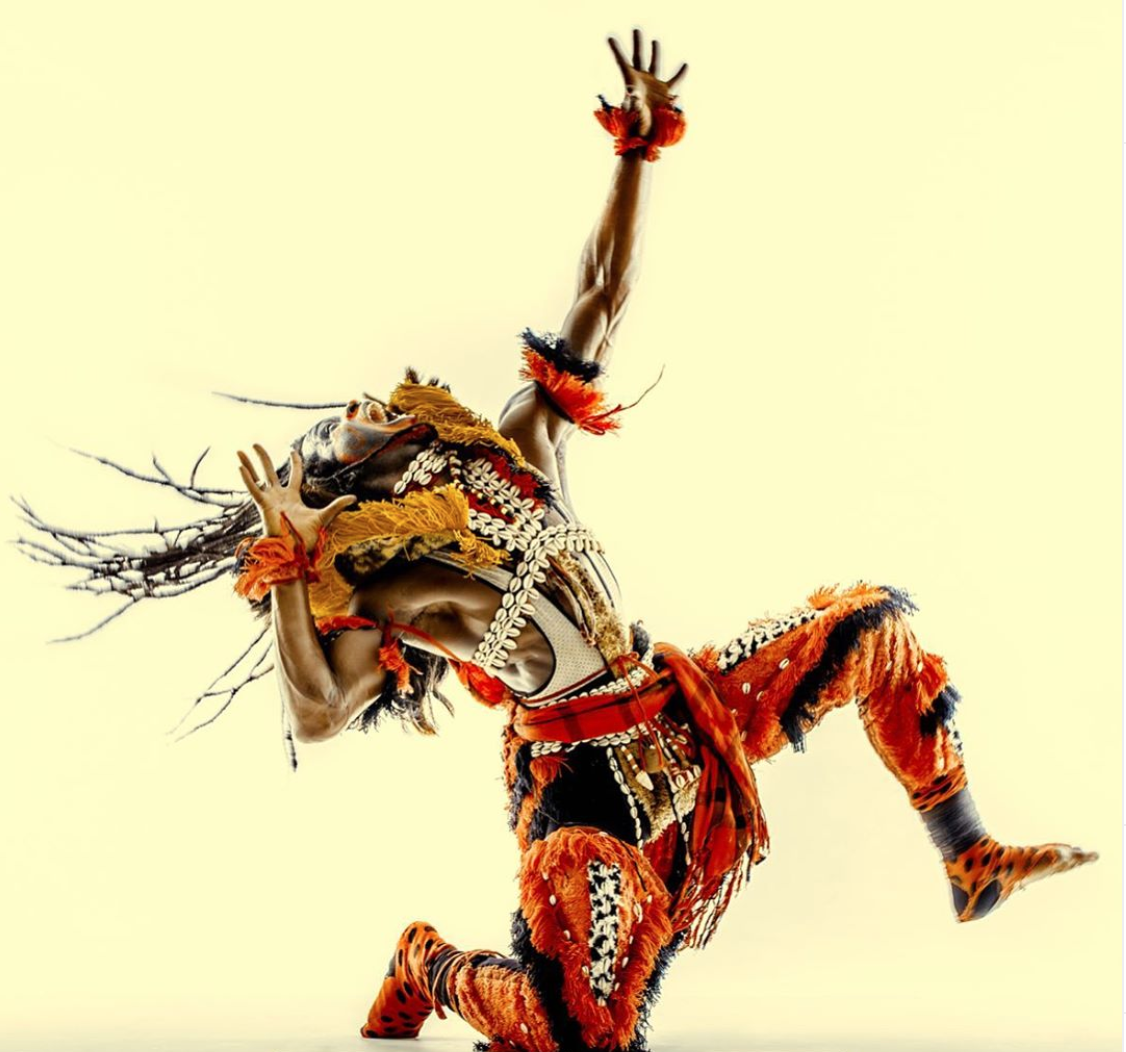

According to the Pedi tradition some Baroka blow a magical horn facing east. Apart from a magical horn, clay pots and also gourds and grindstones are tools used by rainmakers. The grindstone is for grinding the different medicines that then are stirred into the clay pot filled with rainwater. The exact composition of these medicines varies from group to group and from rainmaker to rainmaker.

Immediately after the moroka has performed the ritual of rainmaking, then he or she informs the chief of the day and the makgamankatsana [virgin girls and boys] who then perform the last phase of rainmaking. During that time the makgamankatsana, accompanied by elders, strike the ground with sticks and pour water from the gourds on each corner of the village, performing what is called go phoka pula [to invoke rain]. The makgamankatsana then walk the streets towards each corner of the village, shouting 'pula' 'pula' 'pula' (rain, rain, rain) several times.

Songs are sung by the makgamankatsana along the streets. One of the songs usually sung is:

Pula tsa borare joooo (x2) [Oh! The rain of our fathers](x2)

Pula tsa borare ga e ka na (x2) [if the rain of our fathers could rain] (x2)

Ya na ka medupi [If it could rain unstoppably]

Rena ra tsoga re gata monola [so that we may walk on the nourished ground]

In most cases there is evidence that it rained immediately or weeks later after the rituals were performed.

David K. Semenya