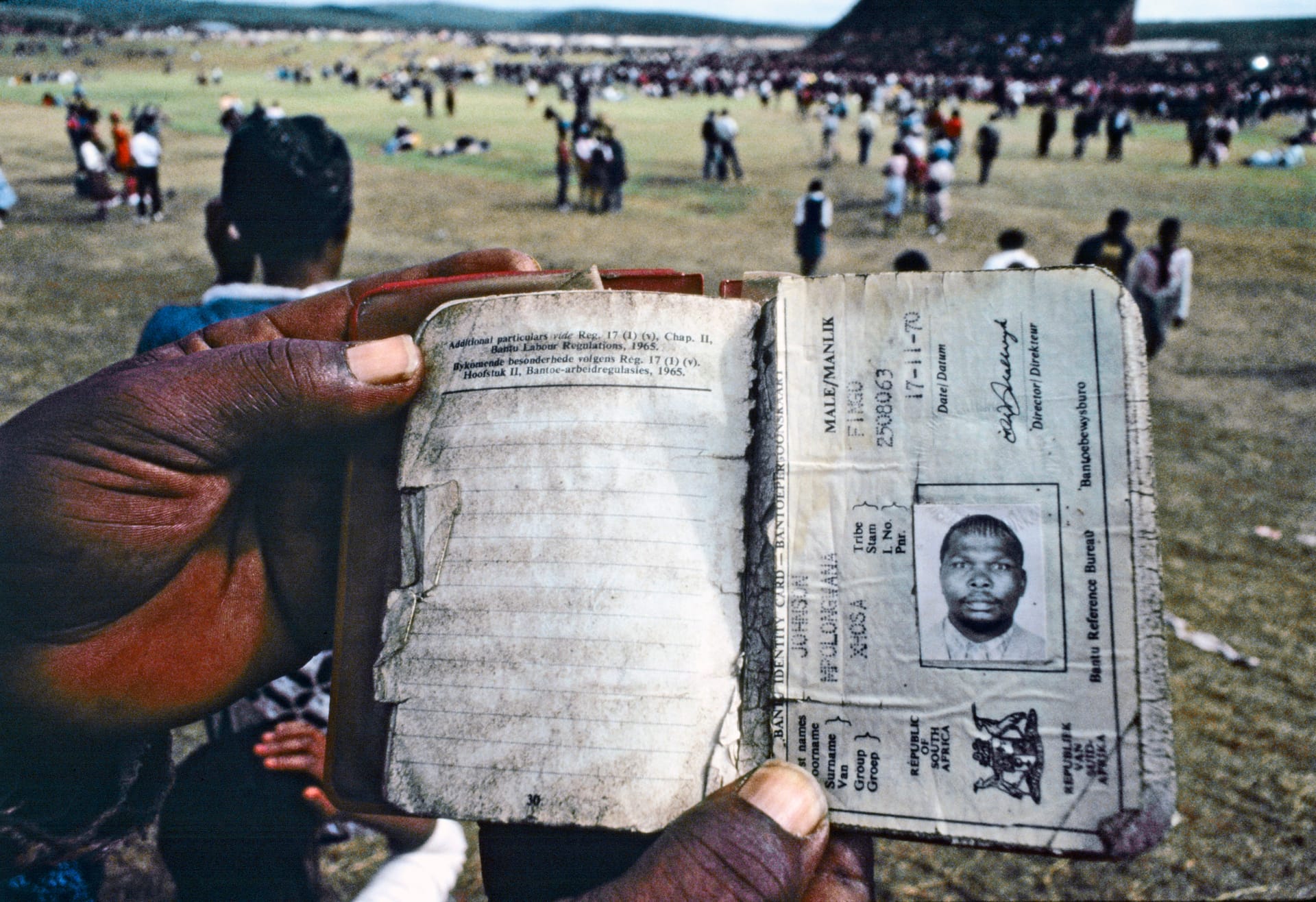

Culture shapes us into who we are, and we, in turn, construct culture. Language plays an important role in the understanding of ourselves as a culture. Language and culture are inseparable. ‘Language is part of culture’.1 ‘No language can exist unless it is steeped in the context of culture; and no culture can exist which does not have at its centre, the structure of natural language’.2 Called it an exit valve3 through which people’s beliefs and thoughts, and cognition and experiences are articulated. It serves not only for communication and sharing of ideas; it goes further to shape as well as to guide the experiences of those who use it.

One linguistic device that has been in use among African communities, who relied mostly on oral culture, is the proverb. A proverb is not simply a tool to advance and enhance good communication; it is also regarded as a deep symbol within culture that reveals the world view of the people. One proverb, in popular use among the Basotho of Lesotho, is Lebitso lebe-ke seromo. Literally translated: ‘A bad name is ominous’. What this proverb reveals about the African world view in general and that of the Basotho in particular is that a name is more than just a social identifier. It serves to represent reality and through it reality is known.

As a sign, it points towards the individual who is signified by the name within the linguistic structures and patterns provided by culture. Over and above its identification and differentiation roles, the name also holds an immense spiritual power to ‘reflect and indexicalise the lives and behavior of people either positively or 4, it carries the very being of a person. In the context of what students of cultural anthropology and sociology of religion call presentational symbolism, a name has an inherent ability not only to point towards what the name signifies but also to generate or bring about what the name signifies 5.

Because a name carries such an immense power, and for that matter the soul of a person, it could determine a person’s destiny. A good name spelt a bright future and in the same vein a bad name, except if it is given for preventative1 or survival reasons 6, was a bad omen to the child. It is in this sense that a name could be considered to be ominous. It was within this context that sorceries or witchcraft practices could be effected on people by the mere use of a name, without the owner’s presence.

Authors: Paul L. Leshota1 Maximus M. Sefotho2

Citing for the Extract:

Leshota, P.L. & Sefotho, M.M., 2020, ‘Being differently abled: Disability through the lens of hierarchy of binaries and Bitso-lebe-ke Seromo’, African Journal of Disability 9(0), a643. https://doi.org/ 10.4102/ajod.v9i0.643

Citing in the Extract

1 Mphande, L., 2006, ‘Naming and linguistic Africanisms in African American culture’, in J. Mugane et al. (eds.), Selected proceedings of the 35th annual conference in African Linguistics, pp. 103–113, Cascadilla Proceedings Project, Somerville, MA.

3 Agyekum, K., 2006, ‘The sociolinguistics of Akan personal names’, Nordic Journal of African Studies 15(2), 206–235.

4Lotman, Y., 1978, ‘On the semiotic mechanism of culture’, New Literary History 9(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.2307/468571

5 Hubbeling, H.G., 2009, Symbols as representation and presentation, viewed 04 April 2016, from https://doi.org/10.1515/nzst.1985.27.1.82

What is your take? What is in your name? Who were you named after? What was happening when you were born and your parents felt it will be important to mark such events in your name?